All my scholarship is copyrighted at the U.S. Library of Congress.

Yale is the only “university” in the world where there is NO dissertation defense, which means that:

1) they can perjure themselves and give false witness against you;

2) they can deny the objective facts, i.e. your academic degrees and official recommendation letters from known scholars like Prof. George Lakoff in the Linguistics dep’t at U.C. Berkeley;

3) they can steal your money and intellectual property, committing a multi-million dollar academic and financial fraud by depriving you — and all the family members who depend on you — of your well-deserved academic work, a lifetime of salary, book sales and conference fees, retirement and health-care benefits;

4) they can maliciously slander you both personally with other so-called “academicians” — i.e. their friends and accomplices, other white-trash academic frauds — and publicly, all over the world, abusing the Internet;

In this way, they believe — but that’s just an article of blind faith, and an irrational belief — that they can conceal the racist crimes of their friends e.g. Mazzotta and Saussy.

White-trash criminals like Leslie Brisman, see the multi-million dollar financial scam related to Prof. Lakoff below, have been aiding and abetting racist sex-offenders at Yale, e.g. Mazzotta and Saussy, as they keep molesting and discriminating against Africans and other people of color, women and the LGBTQIA+ community. Even little children in the New Haven area have become targets of violence and racist hatred from so-called “faculty” at Yale, as in the case of James Lara and his white-trash friend and supporter, Miss Kathryn Lofton.

By giving false witness against the victims of rape, they would like to silence the powerful voices of Africans and other racially diverse scholars — but that’s never going to happen.

From an Afro-centric perspective, my academic fields are:

Dante; Shakespeare; Joyce; Renaissance Art and Literature;

English Lang. & Literatures in English

Italian Lang. & Lit.; French Lang. & Lit.; German Lang. & Lit.

Globalism and international citizenship

World literatures in English translation

The historical method applied to comparative literatures

The European literary tradition in English translation

U.S. culture, society and their media

Foreign language acquisition

Certified translation

Literary translation

Professional editing

Academic research; Academic writing

Creative writing; Online writing and editing

Irony and biting satire against academic corruption, and against racial and sexual violence

Website developer, see my secure websites:

https://margheritamaletiviggiano.com

https://margheritaviggiano.com

LET’S TALK ABOUT SOME OBJECTIVE FACTS:

My Academic Resume w/ George Lakoff’s Recommendation to Yale for his Metaphor Class at U.C. Berkeley

During my study at the University of Bologna, est. 1088. I won an international competition based on academic merit to study at U.C. Berkeley on a full fellowship in the Dep’t of Linguistics, when it was still top rated in the United States. For both semesters, fall 2002 and spring 2003, my high GPA qualified me to be on the Dean’s Honors List.

EXHIBIT

U.C. Berkeley, Official Transcripts, fall 2002 – spring 2003.

As shown here, my GPA was equal or above 3.93 in a full load of letter-graded courses for both the fall semester 2002 and the spring semester 2003, which placed me in the top 4% of students in the College of Letters and Science, see also Dean Kwong-loi Shun’s letter below.

In the fall semester 2002, my classes were:

Linguistics, Metaphor w/ George Lakoff (A); Advanced French (A); Intro to Computers (A-); Advanced German (A).

In the spring semester 2003, my classes were:

English Seminar on James Joyce w/ John Bishop (A); Sociolinguistics w/ Robin Lakoff (A-); Advanced French (A); Advanced German (A).

EXHIBIT

Dean Kwong-loi Shun’s letter on March 5, 2003.

According to Dean Kwong-loi Shun, “This is a remarkable accomplishment. In order to perform so exceptionally, you must have put many long hours of hard work and study.

I trust that you are as gratified with the results as I am. It gives me great pleasure to place your name on the Letters and Science Dean’s Honors List as a recognition of your achievement. I hope that you continue to find Berkeley an intellectually stimulating environment.

It is the interaction at all levels of students like you with our faculty and staff that helps make Berkeley the exciting place we all feel it is. You will find that your excellent record of accomplishment can open new doors to you. I hope your will investigate the many scholarship and research opportunities listed on the Dean’s Honor List web page, etc.”

Now, I’m sure it was not Dean Kwong-loi Shu’s intention, but his words sound ominous for a victim of rape and sex trafficking. Dean Shu was probably not aware of the fact that I had performed at the highest academic levels despite the fact that I had been sexually molested by one of the so-called professors in the English dep’t, acting with the full complicity of his senior colleagues.

When Dean Shu writes that it is “the interaction at all levels of students like [me] with our faculty and staff” that makes Berkeley so special, he wasn’t aware of the fact that white-trash sex offenders like John Bishop – and their accomplices, friends and supporters, like Jeffrey Knapp – would actually give a perverted spin to his words.

And when he mentions the power of my objective academic achievements to “open new doors” – as it should always be, in a just society – he didn’t know I was going to be targeted, as a non-binary person of African descent, precisely in one of the private universities on the East Coast that portray themselves as “liberal,” but are in fact full of racist sex offenders such as Saussy and Mazzotta.

EXHIBIT

University of California, Education Abroad Program presents this certificate to Margherita Maleti, in recognition of the successful completion of the academic year abroad at U.C. Berkeley, Spring 2003.

EXHIBIT

George Lakoff’s recommendation letter for the graduate program at Yale.

The U.C. Berkeley course I took with George Lakoff in the dep’t of Linguistics was on Metaphor, his main academic interest, and my final grade was A+, which was the highest grade.

This is Lakoff’s recommendation letter for Yale:

“It is a real pleasure to recommend Margherita Maleti for admission to your Ph.D. program. Ms. Maleti was a student in my course on Metaphor (Linguistics 106) in the fall of 2002. She was one of the two best students in the course, which is saying something since the students in that course were excellent overall. [She] is no ordinary student. She doesn’t merely learn the subject matter – she interrogates it, shines bright light in its eyes, and makes it confess every hint of inadequacy.

Her term paper on Dante was brilliant, insightful, masterful. But what I remember most was her questions in class. Never pedestrian. Always coming at a topic from a new angle, almost always catching me off my feet, forcing me to confront issues I hadn’t thought about before.

What I especially appreciate about [her] is her intellectual persistence. When she asks a question, she expects a full, serious, thoughtful answer every time, and doesn’t let up until she gets one. Not in an offensive way. Quite the opposite, with a seriousness of purpose, a genuine questioning that one can’t help but respect. I hope you admit Ms. Maleti to your program. She will make a lively intellectual addition to your department, and I think she is destined to become an outstanding scholar.”

First of all, it’s important to notice Lakoff’s reference to my Dante essay: “brilliant, insightful, masterful.”

Indeed, I scanned the entire Divine Comedy for metaphors – something that can only be accomplished with previous knowledge of that massive literary work, which had been part of my cultural background for years.

And that shall put an end to academic and financial scams like Giuseppe Mazzotta and ‘The Goodfellas.’

But what Lakoff fails to mention, here, is the fact that the other student he compares me with was a white male, who was born and raised in the United States and very familiar with U.S. colleges/universities. By comparison, and to be fair, that was the first time for me in a U.S. college/university as a non-binary person of African descent. And that was not an English class, but a Linguistics class that took complete mastery of American English and American culture for granted. But as shown in Lakoff’s letter, my questions ‘almost caught him off his feet.’

And people who ask intelligent questions are often un-welcome, especially if they’re not white.

One of the main questions about Lakoff’s class had to do with his choice of a teaching assistant: a woman in her fifties who used to claim in public to be Lakoff’s “intimate friend.” How’s that professional or even legal, exactly? And does this have anything to do with the fact that his wife, Robin, later divorced him?

There were many other questions having to do w/ relaxed ethical standards. For instance, Lakoff’s background was in linguistics and he knew nothing about the medical sciences. In spite of that, he would make many undemonstrated claims about the neural sciences, with no academic qualifications to back that up.

Furthermore, Lakoff ignored U.S. laws on conflict of interests and lobbied to have his wife, Robin, hired in the very same dep’t of Linguistics at Berkeley, doing exactly the same things, so that salary and benefits were double but authorship was ambiguous at best. And the main victims, of course, were other women who didn’t have a “spouse” or “relative” as an insider. This cannot, and does not, happen in European universities.

That’s just another academic and financial fraud made in the U.S.

These are all intellectually probing questions that reveal a lot about American so-called “academia” and what is officially presented as a “country of laws,” even though the evidence doesn’t support that conclusion.

And people who ask probing questions that go at the heart of the problem, and make people feel very uncomfortable about their hypocrisy, are too often un-welcome, especially if they’re Africans and non-binary.

Another research area for Lakoff was “empathy” – of all possible topics – which he presented as a moving force in politics as well. Here’s an interesting quote from one of his interviews online:

“Empathy is why we have the values of freedom, fairness, and equality – for everyone, not just for certain individuals. If we put ourselves in the shoes of others, we will want them to be free and treated fairly. Empathy with all leads to equality: nobody should be treated worse than anyone else.” “Progressive ideals are based on empathy,” cf. Exhibit below.

Yale and Berkeley present themselves as progressive, or rather, with a façade of progressivism. But the truth is that “empathy,” “fairness” and “justice” is certainly NOT how I was treated by the racist sex offenders denounced in this Criminal Complaint.

That was in fact racist violence and blatant injustice.

And that’s NOT how I was treated by many individuals – including many fake feminists – who helped the sex offenders either loudly and hysterically, e.g. Jane Levin and Kathryn Lofton; or through the code of silence, as the many would-be “academicians” who just watched and let it happen, in typical mafia-style, always hoping to get some money and academic favors out of the situation.

But these crimes are not going to go unpunished, and white-trash criminals go to jail.

EXHIBIT

White-trash criminals like Leslie Brisman tried to turn my academic record upside down, denying the objective facts and the objective evidence.

Leslie Brisman is a white-trash racist, plagiarist and academic fraud who maliciously slandered me as a “Voodoo Nigger with demons,” blocking my dissertation with the false and illegal claim that I didn’t know metaphors, cf. Prof. George Lakoff’s recommendation letter above.

That’s a multi-million dollar financial fraud as well as a racist hate crime.

The truth is that one of my recommenders for Yale was precisely Prof. George Lakoff, from the U.C. Berkeley Linguistics dep’t, and the class I attended with him was precisely on Metaphor, see official transcripts and his recommendation letter above.

Numbers don’t lie and they prove and demonstrate, as another objective fact, that Leslie Brisman has never produced one single African scholar in his entire, irrelevant “career” as the best un-known scholar of Shakespeare.

Throughout his worthless, irrelevant career as the best-unknown scholar virtually in any field, Brisman has always abused and defamed Africans and other people of color, giving false witness against them in order to destroy their career and cover up for his rapists friends.

Indeed, a white-trash racist and plagiarist like Brisman should be denounced and condemned to pay for all his racist crimes in the name of Justice, social justice, anti-racism, and equality.

Numbers don’t lie and they prove and demonstrate, as another objective fact,

that Leslie Brisman has never produced one single African scholar in his entire, irrelevant “career.”

SWINE DECONSTRUCTION

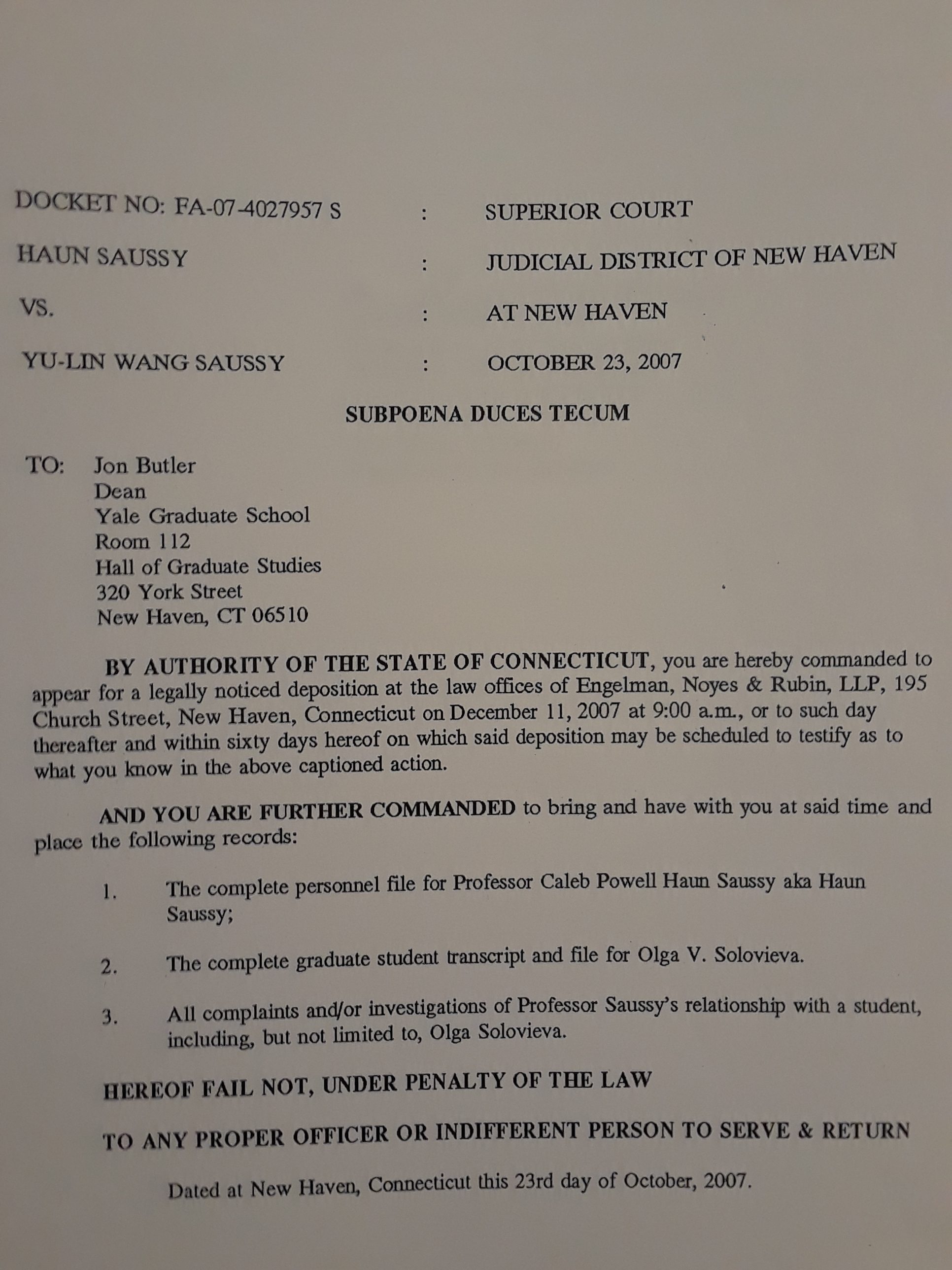

In terms of “full disclosure” or lack thereof, none of this would have ever happened if Richard and Jane Levin had been transparent about Saussy’s affiliation with the KKK. Saussy’s father, Tupper Saussy, was a convicted felon, a KKK member, a crazy conspiracy theorist, and an intimate friend and biographer of the same James Earl Ray who murdered Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

No less than the murderer of MLK!!!

If this fact had been made public, as it is required by law,

I would NEVER even have considered a racist and corrupt dep’t like comparative literature at Yale.

After Yale fired and kicked out both Saussy and his ignorant Russian mistress, Miss Olga Solovieva — with her nonsensical dissertation on the “Body of Christ” supervised, or rather plagiarized, by Saussy himself, just to get her passed — both of them are still in close contact with students and scholars at the University of Chicago, creating situations of danger especially for Africans and other people of color, women and the LGBTQIA+ community.

How do you like the “Body of Christ,” Brisman?

Is Miss Solovieva a “Voodoo Nigger with demons”?

No, she’s just the crazy, old bitch of an insider,

so she must keep stealing money from Africans and other students and scholars of color, right?

***

Here’s another “Voodoo Nigger with demons,” J.K. Rowling, the richest English writer.

And Christopher Marlowe, and Tolkien, and Goethe, and Dostoevsky — all “Voodoo Niggers with demons.”

But what the fuck does ignorant and bigoted Brisman know about European literary history?

ABSOLUTELY NOTHING

And Stranger Things, American Horror Story, Twin Peaks, etc. — in fact, the vast majority of Hollywood & Disney production have elements of magic in them.

All “Voodoo Niggers with demons,” according to racist, white-trash Brisman.

YOUR SCAM IS OVER!

Fernanda Lopez Aguilar, another victim of racism and rape at Yale,

at the hands of a white-trash racist and academic fraud called Thomas Pogge.

These racist sex offenders always target people of color!

We must put an end to rape on campus, and it all starts by telling the truth!

Hamlet and the Pact with the Devil

My academic life changed early on, when I understood that Hamlet’s “ghost” is not a “soul from Purgatory” but in fact a demon, and I assumed everyone knew as well. As I later found out during my lyceum, that wasn’t the case at all. But if someone did understand the truth in the past, they certainly did not write a critical analysis about it – perhaps because they didn’t want to experience the same violence and discrimination I had to experience in a bigoted, racist and white-trash environment like Yale.

Indeed, nobody has ever written this original critical analysis of Hamlet except myself, and I copyrighted it at the Library of Congress in 2013-4, more than four centuries after the play was written (1599-1601), and for the very first time in the history of literary criticism. In this way I also showed that Shakespeare and his predecessor on the English stage, Christopher Marlowe, focused on the same topic – i.e. how corrupt individuals chose evil over good in order to get illicit gains – for both of their masterpieces, Hamlet and Dr Faustus (1592) respectively.

I will forever own that valuable copyright – it belongs to me until I die, and I intend to use it for my family.

FYI, there are NO African scholars of Shakespeare. And on top of that, there are NO scholars of Shakespeare whose first language is not English. That’s a big academic and financial scam, especially considering that Shakespeare is marketed as “universal literature” in an attempt to get money and visibility from the printed press, the Internet, movies, television, radio and tons of merch.

The fact that there are no African scholars of Shakespeare does not come as a surprise, given the amount of racism and violent abuse that ethnically diverse scholars have to face. But I’m not going to let some white-trash criminals get away with their repulsive crimes. It’s terrible enough what they did already. And in addition to that, they’d like to destroy all the intellectual work I’ve been doing since I was a child and a teenager – all the sacrifices I made and all the things I deprived myself of when I was 14, 15, 16 – as I was building the foundations of my academic career. But that’s not going to happen, and this is the end of their academic and financial scam.

Let’s see why the apparition in Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a demon – as Albert Einstein famously said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t know it well enough.” The apparition is not Hamlet’s hallucination, since a number of people, including the soldiers, can see it on the ramparts of Elsinore’s castle. And it’s definitely not a soul from Purgatory, since souls in Purgatory cannot use their free will to sin anymore. They only exist within the confines of God’s Will, suffering to expiate their own unrepented sins, and offering their prayers to help other mortal souls along their earthly journey, which is a concept known as “intercessory prayer.” But contrary to this, and far from helping Hamlet in his quest for justice, the apparition commits a mortal sin by pushing the prince to take revenge and murder King Claudius. In this way, we see that the origin of the apparition is not divine, but demonic.

Everyone in the world who wants to learn English must deal with Shakespeare’s plays at one point, particularly with his masterpiece, Hamlet. In this light, people can understand how much money is involved in this academic and financial scam, and how much these white-trash criminals would like to see me dead.

But time is on my side: now there’s a big storm coming and I’m the only one with a big umbrella, to use a nice metaphor, as well as a safe and comfortable place where I can take shelter. Hence, my intention is to enjoy watching that crazy circus from a distance, laughing about it with my family.

This breakthrough in criticism did play a significant role in my being targeted for rape and sex trafficking, as these white-trash criminals and plagiarists also tried to steal my intellectual property, recycling and repackaging it for themselves, e.g. Saussy, Giuseppe Mazzotta, Jeffrey Knapp, etc. Rather unsuccessfully, since in the end, I’ve overcome every obstacle and was able to copyright my critical analysis at the U.S. Library of Congress. And now, their wishful thinking and plagiarist dreams have become much more difficult to realize in practice.

Chapter III

Hamlet: the “Imperial Theme”

“The spirit that I have seen

May be the devil, and the devil hath power

T’assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps,

Out of my weakness and my melancholy –

As he is very potent with such spirits –

Abuses me to damn me.” (Hamlet II, ii, 600-605)

***

“To hell, allegiance! Vows to the blackest devil!

Conscience and grace to the profoundest pit!

I dare damnation. To this point I stand,

That both the worlds I give to negligence,

Let come what comes. Only I’ll be revenged

Most thoroughly for my father.” (Hamlet IV, v, 128-134)

In the previous chapter we discussed the importance of truthful images in Shakespeare, often contrasted with their opposite, the mask of hypocrisy. Hamlet as a tragedy revolves around the necessity to discern between truthful and deceitful images; hence our first discussion of the play will be devoted to that theme. Then, after contextualizing Shakespeare’s inscription into the European tradition of liturgical drama and Biblical sublime, we will see how the principles of Demonology can enlighten Shakespeare’s masterpiece Hamlet, also clarifying what has sometimes been regarded as mysterious and incomprehensible, i.e. the complex quality of Hamlet’s personality and the many irrational actions he performs.

Shakespeare’s images, a “mirror up to nature”

The capacity to discern between truth and deception, virtue and hypocrisy, is one of the essential themes in Hamlet. Images constitute the interface between the Prince and every other character in the play, including his relationship with himself. If truthful like Ophelia and Horatio, they can function as a “mirror up to nature” (III, ii, 22) in which Hamlet can understand himself and reality. If deceitful like the ghost, instead, they have the power to threaten his life.

To his friend Horatio, Hamlet confides: “But I am very sorry, good Horatio,/ That to Laertes I forgot myself/ For by the image of my cause I see the portraiture of his” (V, ii, 76-78). Hamlet’s personal experience, which he calls the “image” of his existential situation, as it is reflected in his conscience and awareness, is able to make him understand Laertes’s predicament: especially since it was caused by Hamlet himself, when he rashly killed Polonius and orphaned his beloved Ophelia, thus making himself similar to the tyrant and murderer he was desperately trying to punish. Laertes’s tragedy can therefore be observed and understood as a painting or “portraiture,” in which the meaning is clear but at the same time tragically ironic.

Again, Hamlet throws accusations against innocent Ophelia with the intention to hurt his mother the Queen indirectly, by the reported speech of the awkward spy Polonius. He does so by using the image of face painting: “I have heard of your paintings, too, well enough. God has given you one face, and you made yourselves another” (III, i, 145-147). Ophelia, perhaps the only character in the play who is not able to pretend, is paradoxically accused of being a hypocrite. Interestingly, the hypocrite Claudius uses the same image of the painted prostitute, whose Scriptural referent is the Great Babylon of worldly corruption, to describe his fratricide and the deceitful words with which he managed to cover it all up: “How smart a lash that speech doth give to my conscience./ The harlot’s cheek, beautied with plast’ring art,/ Is not more ugly to the thing that helps it/ Than is my deed to my most painted word./ O heavy burden!” (III, i, 52-56)

Truthful and deceitful images perform a primary role in the relationship between the Prince and his mother Queen Gertrude. In her bedchamber after The Mousetrap, Hamlet tells her that he intends to set up a “glass” to her conscience, that she may realize how tarnished it is: “You go not till I set you up a glass,/ where you may see the inmost part of you” (III, iv, 19-20). In the same way, a couple of scenes before, Hamlet instructs the players on dramatic art, whose purpose it is to imitate nature truthfully and without exaggeration – Shakespeare’s poetics of realism: “anything… overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is to hold as ‘twere the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure” (III, ii, 20-24).

Hamlet invites Gertrude to compare the images of the two brothers: the picture she wears of the murderer and the picture he wears of the murdered king – a repetition of history in its primal scene of betrayal and fratricide with Cain and Abel:

“Look here upon this picture, and on this,

The counterfeit presentment of two brothers.

See what a grace was seated in this brow […]

A combination and a form indeed

Where every god did seem to set his seal

To give the world assurance of a man.

This was your husband. Look you now what follows.

Here is your husband, like a mildewed ear

Blasting his wholesome brother. Have you eyes?

Could you on this fair mountain leave to feed,

And batten on this moor? Ha, have you eyes?” (III, iv, 52-66)

It is interesting to see that Hamlet compares the two opposite images in the context of Demonology, asking Gertrude: “What devil was’t/ that thus hath cozened you at hood-man blind?/ O shame, where is thy blush? Rebellious hell/ if thou canst mutine in a matron’s bones,/ To flaming youth let virtue be as wax/ and melt in her own fire. Proclaim no shame/ When the compulsive ardour gives the charge,/ Since frost itself as actively doth burn,/ And reason panders will” (70-78); and again: “Confess yourself to heaven;/ Repent what’s past, avoid what is to come” (140-141), “And when you are desirous to be blest,/ I’ll blessing beg of you.” (155-156) The Scriptural reference is to the Pauline Letters, in particular the first Letter to the Corinthians, where Paul gives advice on marriage and celibacy. Because “time is running out” (1 Cor 29-31) at the fast approach of individual death, and on a larger scale with Christ’s Second Advent and Last Judgment, the Apostles expresses his view that preserving one’s virginity is preferable unless someone lives “under compulsion,” the compulsion of demonic agency, cf. Amorth on demonic oppression (Chapter Two) and the uncommon strength of its temptation experienced as even something “vital,” “natural” “irresistible” and “constructive” – “If anyone thinks he is behaving improperly towards his virgin… he is committing no crime; let them get married. The one who stands firm in his resolve, however, who is not under compulsion but has power over his own will… will be doing well. So then, the one who marries his virgin does well; the one who does not marry her will do better” (1 Cor 36-38)

After hearing Hamlet, Gertrude looks at the images of the two brothers from a new perspective, and replies in agony: “O Hamlet, speak no more!/ Thou turn’st mine eyes into my very soul,/ And there I see such black and grainèd spots/ As will not leave their tinct” (78-80); “O Hamlet, thou has cleft my heart in twain” (147); “O speak to me no more!/These words like daggers enter in mine ears” (84-85). With the image of “ears” Shakespeare suggests that, by means of her silent acceptance, Gertrude has become an accomplice of Claudius’ murder as he poured poison into his brother’s ears. This is the crucial moment of Gertrude’s conversion, when she finally admits her share of responsibility. By refusing to know the truth about the crime, as long she could keep her position and her privileges at court, she made herself an accomplice of fratricide. But after this scene Gertrude does not betray Hamlet’s secret, that he is “essentially… not in madness,/ But mad in craft.” (171-172) Hence she swears, with lines that prefigure her death – a tragic omission of help by Claudius and Hamlet, both aware of the poisoned cup – “Be thou assured, if words be made of breath,/ And breath of life, I have no life to breathe/ What thou hast said to me.” (181-183) By means of a superlative performance and the use of images, Hamlet manages to call her mother to repentance – showing to her mind’s eye how her generous and brave husband was to his cowardly brother like “Hyperion to a satyr” (I, ii, 140).

It is essential to appreciate the importance of images in this scene. Gertrude repents by virtue of a comparison of the two portraits, as well as being moved by two other images of death and final judgment which Hamlet unwittingly provides: his rash murder of Polonius and his dialogue with the ghost. Confronted with these images, Gertrude is in fear and trembling and she cannot deny the remorse of her tainted conscience, anguished at the thought of the impending death and judgment. Shakespeare’s art gains depth and substance from this ethical realism, which affords us a deeper understanding – hence a greater pleasure – of the complexity of reality, as well as of the dark human heart that forms and de-forms history.

This crucial scene shows that Shakespeare had, by the time he composed his masterpiece, developed a solid and subtle understanding of the power of images – which is only to be expected in a sublime artist conscious of his task and work instruments. In fact, there are indications that he conceived of such power as something divinely ordained, pertaining to the very manner in which God formed humanity. In the meta-dialogue with the acting troupe, for instance, Hamlet remarks: “… mine uncle is King of Denmark, and those who would make mows at him while my father lived [now] give twenty, forty, an hundred ducats apiece for his picture in little. ‘Sblood, there is something in this more than natural, if philosophy could find it out.” (II, ii, 363-368) But the supernatural is not the realm of philosophy – and it is only partially discerned from the higher observatory of theology.

It is precisely in Hamlet’s interaction with the players that the theme of images and artistic mimesis comes to the fore in the form of meta-writing. These meta-scenes offer a truthful image and “portraiture” of Shakespeare’s poetics and work-ethics; while at the same time representing a moment of self-reflection of the play upon itself. Here Hamlet the character “mirrors” Shakespeare the author in the same way as the author “mirrors” God’s recreation of Himself within His own creation – first in the Incarnation, then in the Transubstantiation – through His most perfect creature, the Virgin, Mother of all the elect in the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church. Also God is “all in all” in all of His creatures.

Wanting to discover the truth, and direct his course of action accordingly, Hamlet creates a truthful image and artistic mimesis with The Mousetrap, taking inspiration from an “extant” story “writ in choice Italian.” (III, ii, 250-251) His artistic image “mirrors” reality in order to denounce it – denouncing to the world how the dead King was betrayed, murdered and forgotten by the people who were supposed to be most loyal to him, in one of the numberless power-plots recorded in the “gore-scarred” book of bloody history.[i]

Vaguely remembering the Scripture passage on Lucifer masquerading as an “angel of light” and his demonic subjects masquerading as “ministers of righteousness” (2 Cor 11:14), Hamlet suspects that the spirit he saw may be a demon disguised as the penitent soul of his father, as demons are able to do: “The spirit that I have seen/ may be the devil, and the devil hath power/ T’assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps,/ Out of my weakness and my melancholy –/ as he is very potent with such spirits –/ Abuses me to damn me.” (III, i, 600-605). But Hamlet also believes, with a superb non sequitur, that if the spirit’s revelations regarding Claudius are correct, he is justified in taking revenge by murdering the murderer.

Truthful images allow to know the truth and achieve a certain degree of cognitive certainty – as Hamlet says, “I’ll have these players/ Play something like the murder of my father/ Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks… The play’s the thing/ Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.” (III, i, 596-607). But data about the supernatural gathered by means of truthful images also need to be interpreted within the correct supernatural context, i.e. Catholic theology and Demonology, and when that context is lacking, the resulting action is not successful, as in the case of Hamlet’s revenge. It is through images that Hamlet comes to know the truth, acting on it more or less appropriately. Hence we see that images, mimetic art and theatrical mimesis in particular become in Hamlet the pivotal center – its center of gravity, as it were. As in a Renaissance court, where simulation and dissimulation are the rule and modus operandi, truthful and deceiving images are the very essence of Hamlet. It is thanks to the “mirror up to nature” of The Mousetrap that Hamlet discovers the truth about the corruption of the world surrounding him; and it is thanks to the tragic image of orphaned Laertes that he conceptualizes his own existential predicament in that world.

Always in the interaction with the players (Act II, scene ii) the image of wild Pyrrhus slaughtering the royal house of Troy and murdering both King Priam and Queen Hecuba functions as a prophetic mirror-image of Hamlet’s own situation. Hamlet fears that the compact of vengeance with the ghost will force him to become another Pyrrhus, killing both Claudius and his own mother. And he is right – the Pyrrhus prophecy is fulfilled. The noble Prince himself turns into a tyrant by killing… almost everybody, in fact. One person in revenge, Claudius, by forcing him to drink to the dregs the Cup of God’s Wrath, so to speak, cf. Jer 25; Rev 14. Three people more or less in self-defense: the two spies Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and Laertes after he cheated in combat using the poisoned sword. And other three victims completely gratuitously: Polonius, the father of Laertes and Ophelia; Ophelia, who took her life after being orphaned and abandoned by a “mad” lover like the maid Barbary in Desdemona’s story; as well as his own mother Gertrude – for if Hamlet suspected that the cup had been poisoned by Claudius, why did he let her drink?

In his understanding of images as prophecies and prophecies as images, Shakespeare was guided by the nature of Scriptural prophecy, often of a poetic quality – from Isaiah and the Psalms of David, to the Pauline Letters and the Apocalypse of John. Indeed, the only Books that present a lower incidence of images are the historical books of the Bible, and even there historical events function as Christological prefigurations – as in Judith and Esther, powerful figurae Mariae, and the sacrifice of Jephthah’s daughter. (Chapter Two) In Scripture, symbolic images are God’s preferred way to make His Infinity understood by the limited cognitive capacity of fallen humanity. By virtue of images, complex meanings can quickly be understood and recalled to mind, e.g. the visions of Moses in the desert, Jacob’s dream, the dream of Mordecai and Daniel’s visions of the Second Advent and Last Judgment, etc.

The Judeo-Christian and Classical traditions converge here, since symbolic images abound in Plato’s works, e.g. the allegory of the cave, and also Aristotle comments in his Poetics that “by far the most important matter is to have skill in the use of metaphor,” as it “cannot be acquired from another” and by itself is a “sign of natural gifts,” denoting an ability to “discern similarities” among different objects of observation (1459a5-8).

Images can be used to manifest virtue or to mask vice with a show of hypocrisy. The character of Polonius embodies both. In the play he appears as a foolish courtier who deludes first of all himself thinking that he is acting for the wellbeing of others, while in fact pursuing his personal profit. He is by no means innocent. To Reynaldo, for instance, whom he pays to slander Laertes during his Paris trip, he confides: “Your bait of falsehood takes this carp of truth;/ And thus do we… By indirections find directions out” (II, i, 602-65). It is open to interpretation whether slander really is the best way to promote the good reputation of one’s son abroad – but, as it often happens in this meta-tragedy, the words prove valid if we understand them more generally as coming from the author’s perspective, for indeed Shakespeare’s ethical theater is a “bait of falsehood” to catch the truth. And Polonius can also be seen as a more sympathetic character. In one of his mad dialogues with Hamlet, when Hamlet plays the fool to someone more foolish than himself, Polonius unwittingly utters a prophecy on his own death:

“Hamlet. […] My lord, you played once i’th’ university, you say.

Polonius. That I did, my lord, and was accounted a good actor.

Hamlet. And what did you enact?

Polonius. I did enact Julius Caesar. I was killed i’th’ Capitol. Brutus killed me.” (III, ii, 94-100)

This is a prophecy for the benefit of audience and readers alone, since neither Polonius nor Hamlet will ever become aware, in the course of the play, of how it is fulfilled. As such, this is Shakespeare’s running commentary on his own art, as he reaches out from the stage or the page to our present reality, eternalizing himself. In this meta-scene on acting, Polonius takes pride in saying that as a student he used to play in the university theater, where he interpreted Caesar, betrayed and murdered by Brutus, as Polonius himself will be murdered by a younger man who could be his son. Polonius’s words are a tragically ironic prophecy on both murderer and victim, uttered in perfect ignorance, as we can expect from a fool; but they also possess a deeper meaning if we see them as an authorial invitation to consider the thematic connections between Hamlet and Julius Caesar. It is in fact interesting to notice that both tragedies are about regicide and usurpation, and both feature ghostly apparitions – which are indeed quite rare in Shakespeare, the only other instance being the ghost of Banquo in Macbeth. But it is even more interesting to notice that in all these instances, the “ghosts” of the murdered kings are directly related to the “imperial theme” (Macbeth I, iii, 126-128), denouncing the corruption that is inevitably associated with worldly power – as we will see in the “imperial theme” section of this chapter.

In the main, Polonius unrealistically thinks of himself as wise and shrewd not unlike Malvolio in The Twelfth Night; in fact he is a hypocrite who tries to stage a naïve ploy on the most complex and theatrically-minded character in English literature – even exploiting his daughter’s innocence to do so. Without excusing Hamlet for murdering him unnecessarily, we can see that he actively pursues his own demise by means of his meddling foolishness. His theater of simulation and dissimulation is made of false images throughout, but being humanly false images, they do not fool Hamlet who had a life-long training in the discernment of human falsehood. The spectators of Polonius’s false meta-theater are the “lawful espials” Claudius and Gertrude, who “hear and see the matter” (III, i, 24) “seeing unseen.” (III, i, 35)

This scene represents one of Shakespeare’s leitmotifs: how to discern images of virtue from images of hypocrisy, as we discussed for Othello. Interestingly, in the following lines, Polonius refers to religious hypocrisy in the same way as his daughter Ophelia had previously done, when she warned Laertes to be careful and practice his own moral preaching – unlike “ungracious pastors,” not “shepherds,” who place undue burdens on other people’s conscience while at the same time behaving like “puffed and reckless libertine[s].” Here are the texts:

| “But, good my brother,

Do not, as some ungracious pastors do, Show me the steep and thorny way to heaven Whilst like a puffed and reckless libertine Himself the primrose path of dalliance treads And recks not his own rede.” (I, iii, 46-51)

|

“We are oft to blame in this:

‘Tis too much proved that with devotion’s visage And pious action we do sugar o’er The devil himself.” (III, i, 48-51)

|

Human beings survive and thrive by imitative behavior; hence the capacity to understand the meaning of images, to remember and reproduce them, is essential for human cognition – and indeed Renaissance mnemotechnique, at which Giordano Bruno excelled, revolved around images. The tragedy of Hamlet offers false images in overplus, some of which the Prince manages to discern as such, while others lead him astray. As we will see, Hamlet is able to recognize human images of deceit; he is nonetheless unable to discern superhuman ones, for which the “discernment of spirits” is needed as a gift of God’s Holy Spirit.

There is first of all the supernatural deception of the ghost, cf. the following section on Demonology in Hamlet; then the murderous deception, in varying degrees of responsibility, of Claudius and Gertrude; then again the Prince – who at first claims to “know not ‘seem’” and be innocent of “actions that a man might play” for show (I, ii, 76 and 84) – is only too ready to exploit Ophelia by presenting her a deceitful image of himself (II, i, 76-101), persuaded as he is that such wild impersonation will help his cause; again, Polonius organizes a ploy against his own son as well as against Hamlet, deluding himself that he is acting for the good of both; later, Laertes is only too happy to kill Hamlet in a murderous plot, while pretending to fight an honest and loyal duel according to chivalric rules; Rosencrantz and Guildenstern pretend to be Hamlet’s friends while being paid by his mortal fiend Claudius; Fortinbras pretends to lead his army through Denmark peacefully while scheming to overtake it, etc. Indeed, the only characters who are exempted from such overwhelming hypocrisy are Ophelia, the gravediggers and Horatio – Ophelia is a victim of court corruption; the gravediggers are victims of exploitation and the injustice of poverty; Horatio is the only survivor of the play, and to him Hamlet’s story is entrusted to be faithfully narrated to the world.

Having discussed the crucial role of images in Shakespeare, we can inquire what the aim of the author may have been in investing so much of his talent on this theme. Like Machiavelli, Castiglione and Thomas More, Shakespeare lived in a corrupt and violent society, for which knowledge of simulation and dissimulation was needed in order to survive. The vital problem of truthful and deceitful images was first of all connected with the treacherous court environment, and the English court was not different in this than any other European court, including the Vatican. But what was unique to England and Northern Europe at the time was religious schism, religious persecution and iconoclasm – for the victims. The perpetrators instead had to face the arduous problem of how to put on a show of virtue while at the same time falsely accusing and butchering model citizens like Edward Arden and John Somerville. Their problem was how to seem “Christian” monarchs and “defenders of the true faith” while at the same time denying the Scriptural evidence of the apostolic succession from Christ to Simon Peter (Mt 16:13-20); while murdering one’s own wives (Henry VIII); while persecuting, dispossessing, torturing, hanging and disemboweling innocent victims like Robert Southwell (Elizabeth I); while supporting piracy and slavery (Elizabeth I); while setting up bogus-trials for witches, looking on as they were tortured to death (James I). Like Dante, outraged at the corruption of Boniface VIII, Shakespeare must have felt that the times of the Great Tribulation described by Isaiah, Daniel, Zechariah, Matthew and John, among others, were close at hand – and in fact, as we will see, Hamlet contains an apocalyptic subtext. In the context of religious schism and its political-economic significance in Northern Europe, the “imperial theme” was for Shakespeare indissolubly linked to hypocrisy, corruption and mass-murder – to the symbolic “wolves in sheep’s clothing” (Mt 7:15) for whom, like Angelo in Measure for Measure, no measure is ever enough.

Thomas Nashe (1567-c.1601) was a keen observer of the “form and pressure” of the times, a satirizer and fierce critic of worldly corruption in all its guises. Of the same generation and religious loyalty of Shakespeare, Nashe described political terror and religious persecution from the point of view of spying: an activity that always accompanies tyrannical regimes. In The Unfortunate Traveller (1594), Nashe remarks that “a man were better be a hangman than an intelligencer;”[ii] a “sneaking eavesdropper,” “scraping hedge-creeper,” and a “piperly pickthank,” i.e. sycophant. According to Nashe, spies are like new Judases and their race is made of “beggarly contemners of wit,” “huge burly-boned butchers” “good for nothing.”[iii] The energy of his denunciation, here and elsewhere, seems autobiographic as it is in the nature of satiric writing. Nashe himself must have known how necessary it is “to have the art of dissembling at [one’s] fingers’ ends as perfect as any courtier,”[iv] if one wishes to survive in times of terror. And in fact, in a passage about a chivalrous tournament in Italy, Nashe symbolically describes one of the knights as a persecuted Catholic: “A fourth, who, being a person of suspected religion, was continually haunted with intelligencers and spies that thought to prey upon him for that he had, he could not devise which way to shake them off but by making away that he had.”[v]

Nashe was more outspoken than Shakespeare in his condemnation of political and religious hypocrisy and dissimulation – and in fact he did not enjoy a long life. In this passage on how religious orthodoxy had been perverted, Nashe epitomizes the fears of many of his contemporaries who felt close to “the notable Day of the Lord” prophesied in Scripture:

But I pray you let me answer you: doth not Christ say that before the Latter Day the sun shall be turned into darkness and the moon into blood? Whereof what may the meaning be, but that glorious sun of the Gospel shall be eclipsed with the dim cloud of dissimulation; that that which is the brightest planet [the monarchy, esp. the king] of salvation shall be a means of error and darkness? And the moon shall be turned into blood: those that shine fairest [the aristocracy and the clergy], make the simplest show, seem most to favor religion, shall rent out the bowels of the Church, be turned into blood, and all this shall come to pass before the notable Day of the Lord, whereof this age is the eve?[vi]

Notice here Nashe’s indictment of the religious schism, eclipsing “the glorious sun of the Gospel” “with the dim cloud of dissimulation;” notice his explicit denunciation of political and religious corruption as “error and darkness;” notice finally Ophelia-Shakespeare’s own critique against the hypocrisy of “pastors,” who like bad actors “make the simplest show” but in fact “rent out the bowels of the Church.”[vii] As Nashe writes, “those that shine fairest… seem most to favor religion, shall rent out the bowels of the Church.” The Pauline images of Lucifer as “an angel of light” and of his ministers as “false apostles, deceitful workers, who masquerade as apostles of Christ” (2 Cor 11:14 and 13) also describe political and religious corruption, trying to destroy images of the true faith and replace them with false ones, man-made doctrines to follow Mammon, not God. The followers of Christ do not live in ivory palaces while their subjects are victims of poverty, persecution and terror: “Christ would have no followers but such as forsake all and follow him, such as forsake all their own desires, such as abandon all expectations of reward in this world, such as neglected and contemned their lives… in comparison to Him, and were content to take up their cross and follow Him.”[viii]

Shakespeare, biblical sublime and mystery plays

“…there is no basis for a separation of the sublime from the low and every-day, for they are indissolubly connected in Christ’s very life and suffering. Nor is there any basis for concern with the unities of time, place, or action, for there is but one place – the world; and but one action – man’s fall and redemption.” (Mimesis, 158)

The enduring legacy of medieval religious plays and liturgical drama in Renaissance Theater is discussed in Auerbach’s ‘Adam and Eve’ chapter in Mimesis, where he elaborates on Dante’s learned explanation of typology. In his Letter XIII, To Cangrande della Scala, Dante describes the four levels of Scriptural exegesis with the example of Psalm 113: “In exitu Israel de Egipto, domus Iacob de populo barbaro, facta est Iudea sanctification eius, Israel potestas eius.”[ix] Mystery Plays and Passion Plays were grounded in a typological reading of Scripture and human history centered on the figures of Christ as the Messiah and the Virgin as New Eve, whereby every prophecy or prefiguration of the Old Testament finds its fulfillment in Christ’s Incarnation, Passion and Resurrection; His Second Advent and His Last Judgment. This is the orthodoxy represented in liturgical drama from the 14th century on – as discussed by Auerbach, who sees a fundamental similarity between liturgy and theater: the epic history of God’s Incarnation, Passion and Resurrection is daily reenacted in the Mass in a way similar to the modalities of dramatic art itself.

Auerbach defines the Biblical sublime[x] as a stylistic trait of the Logos of Scriptures, fundamentally new and revolutionary if compared to the classical tradition. Scripture unites sermo gravis and sermo remissus in perfect harmony of form and content: “In antique theory, the sublime and elevated style was called sermo gravis or sublimis; the low style was sermo remissus or humilis; the two had to be kept strictly separated. In the world of Christianity, on the other hand, the two are merged, especially in Christ’s Incarnation and Passion, which realize and combine sublimitas and humilitas in overwhelming measure.” Sublimitas and humilitas are categories at the same time theological and aesthetic: “the antithetical fusion of the two was emphasized, as early as the patristic period, as a characteristic of Holy Scripture – especially by Augustine.”[xi] According to Auerbach, “the true and distinctive greatness of Holy Scripture [is] that it had created an entirely new kind of sublimity, in which the everyday and the low were included, not excluded, so that, in style and content, it directly connected the lowest with the highest.”[xii] The Biblical sublime is thus characterized by an unfathomable simplicity, which functions as the mirror image of God’s unfathomable Simplicity, God being One and always equal to Himself – cf. Mal 3:6, Heb 13:8, Rev 1:8 – Simple and Infinite, and infinitely complex. “The Scriptural sublime tends to be ‘simple’ as God Himself is Simple, that is, One. At the same time, Scriptures contain riddles and mysteries which can only be understood by the humble and faithful – metaphorically, by those admitted in through the keys of St Peter [cf. “I give you praise, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, for although You have hidden these things from the wise and the learned, You have revealed them to the childlike. Yes, Father, such has been Your gracious Will,” Lk 10:21] It is only through the keys of faith and humility that man gains insight [cf. Augustine, Confessions, 3,5; 6,5; De Trinitate, I; To Volusianus (137,18)]”[xiii]

The divine sublime is, in human terms, a paradox: a coincidentia oppositorum where the infinitely complex expresses itself through the infinitely simple; where the infinitely great can be found in the infinitely small, and vice versa – God is the Alpha and the Omega, “all in all” – as in the mystery of the Eucharist, where the boundless, infinite Creator is fully present in grains of wheat and drops of wine. The majestic incipit of John’s Gospel is perhaps the best example of this divine paradox – and in his long experience as the Chief Exorcist of the Holy See, Amorth confirms that this passage has the power to terrorize demons: “In the Beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came to be through Him, and without Him nothing came to be. And what came to be with Him was life, and this life was the light of the human race. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (Jn 1:1-5)

This unity of opposites characterizes both the Biblical sublime and the medieval religious plays that take inspiration from it: “The medieval Christian drama falls perfectly within this tradition [of Scriptural sublime simplicity]. Being a living representation of Biblical episodes as contained, with their innately dramatic elements, in the liturgy, it opens its arms invitingly to receive the simple and untutored and to lead them from the concrete, the everyday, to the hidden and the true – precisely as did the great plastic art of the medieval churches which, according to E. Mâle’s well-known theory, is supposed to have received decisive stimuli from the mysteries, that is, from religious drama. […] The scenes which render everyday contemporary life… are then fitted into a Biblical and world-historical frame by whose spirit they are pervaded… the spirit… of the figural interpretation of history. This implies that every occurrence, in all its everyday reality, is simultaneously a part in a world-historical context through which each part is related to every other, and thus is likewise to be regarded as being of all times or above all time.” [xiv]

For Shakespeare’s theater in the Renaissance, the implications are clear. More than applying unrealistic constrictions of time and place on the plot, it is necessary to consider that “every occurrence” in Salvation History “is simultaneously a part in a world-historical context, through which each part is related to every other, and thus is likewise to be regarded as being of all times or above all time” – a particular design forever present in God’s Mind.

The individual tragedies of everyday life and the majestic, tragic movement of universal history both fit into a typological interpretation of reality whose mystical center is the Incarnation, Passion and Resurrection of Christ. With this, God brings us the possibility of redemption after the tragedy of the original sin. He does so with the tragedy of His own martyrdom and death, as a prefiguration of our own. God is the omnipresent I AM, inside and outside time – which is only one of His creatures. Hence Biblical typology covers human history from Creation to the Last Judgment: “[b]efore His appearance, there are the characters and events of the Old Testament… in which the coming of the Saviour is figurally revealed. […] After Christ’s Incarnation and Passion there are the saints, intent upon following in his footsteps, and Christianity… Christ’s promised bride, awaiting the return of the Bridegroom.”[xv]

The drama of bloody human history thus acquires meaning in relation to the Christological drama: “this great drama contains everything that occurs in world history. In it… there is no basis for a separation of the sublime from the low and every-day, for they are indissolubly connected in Christ’s very life and suffering. Nor is there any basis for concern with the unities of time, place, or action, for there is but one place – the world; and but one action – man’s fall and redemption.” For medieval audiences, every episode of Sacred History implied the whole, which was always “borne in mind and figuratively represented.”[xvi]

Auerbach reminds us that the Mystery and Passion Plays as mimesis of the typological vision of history are a powerful dynamic force, both religious and socio-political, “from the fourteenth century on.”[xvii] This derivation from late medieval theater is exceptionally important for Shakespeare and Shakespearean criticism, since the author was accused, over the centuries, of transgressing the Aristotelian unities of time and place, if not of action. In fact, Shakespeare is faithful to the more influential tradition of Christian liturgical drama in which Aristotle himself found meaning as one of the high points of natural light before the divine Light of Revelation.

If every event in the course of human history finds its true significance in light of the Christological epic, it follows that the more realistic way to represent reality is to focus on the unity of action, presenting every event in the context of Salvation History. In his day Shakespeare was similar in this to Lope de Vega (1562 -1635), one of the authors of the Spanish Golden Age. In his “defiant and humorous Arte Nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609), Lope proclaimed his freedom from Aristotelian strictures, abandoning the rigors of what a play ‘should’ be in favor of plays that appealed to the varied audiences of the public playhouses or corrales, where aristocrat and commoner coincided.”[xviii]

Hamlet and demonology, “in this distracted globe”

The hermeneutic key to Hamlet is the identity of the ghost. The tragedy revolves around the identity of the apparition – either divine or demonic. Because demons and demonic subjects can also say the truth, the decisive factor is not, as Hamlet erroneously assumes, to ascertain whether the apparition does, or does not, speak truthfully: “I’ll have the players/ Play something like the murder of my father… If [Claudius] but blench,/ I know my course” (II, ii, 509-600). As spiritual creatures unconstrained by material limits and boundaries, demons have the power to know concealed truths – facts whose knowledge they acquire through the exercise of their intellectual activity, which is superior to that of human beings, as Augustine and Aquinas clarify in their discussions of the principles of Demonology (Chapter Two). Knowing the truth about certain events is irrelevant in terms of discernment between a divine or demonic apparition, e.g. demons know that they are doomed to defeat – the first time with the Passion and Resurrection of Christ; the second time with Christ’s defeat of the Antichrist during the Second Advent; the third and final time with the Last Judgment at the end of human history – and yet they do not cease to be demons only because they know their end. Hence Hamlet is very much misguided when he assumes that comparing the message of the apparition with the facts will enlighten him on the best course of action:

“I’ll have these players

Play something like the murder of my father

Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks,

I’ll tent him to the quick. If a but blench,

I know my course. The spirit that I have seen

May be the devil, and the devil hath power

T’assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps,

Out of my weakness and my melancholy –

As he is very potent with such spirits –

Abuses me to damn me.” (II, ii, 596-605)

The misguided Prince has a correct intuition: “The spirit that I have seen/ May be the devil, and the devil hath power/ T’assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps,/ Out of my weakness and my melancholy –/ As he is very potent with such spirits –/ Abuses me to damn me.” (II, ii, 600-605) Remembering perhaps his own study of Scripture, the numerous sermons heard and people’s common knowledge, cf. Ranald’s socio-cultural context (1987), Hamlet understands that there is a real possibility he might have witnessed a demonic apparition.

How can we realize that the “ghost” is not a penitent soul from Purgatory, but a demon? In his first Letter, John the Evangelist explains: “Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world. This is how you can recognize the Spirit of God: Every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come into the flesh is from God, but every spirit that does not acknowledge Jesus is not from God. This is the spirit of the Antichrist, which you have heard is coming and even now is already in the world.” (1 Jn 4:1-3) This is the hermeneutic key to spiritual discernment: the Logos. The Logos warns: “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but underneath are ravenous wolves. By their fruits you will know them. Do people pick grapes from thorn-bushes, or figs from thistles? Just so, every good tree bears good fruit, and a rotten tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a rotten tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire. So by their fruits you will know them.” (Mt 7:15-20) By his own words the “ghost” betrays his demonic identity – by what he says and what he compels Hamlet to do against God’s Law.

It is against the Law of God to kill and take revenge for crimes suffered. A penitent soul in Purgatory is and always will be in the grace of God. Hence it is impossible that a soul who has been saved and lives in the grace of God should instruct a human being to break the Law of God: “You shall not kill” is the fifth commandment of the Tables of the Law (Ex 20:13, cf. Mt 5:21). Furthermore, vengeance is a prerogative of God as the only righteous Judge: “’Vengeance is Mine; I will repay,’ says the Lord.” (Rm 12:14-19, cf. Lv 19:18; Dt 32:35-41; Mt 5:39; 1 Cor 6:6-7; Heb 10:30) Instead of taking revenge, human beings must forgive: “I say to you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times” (Mt 18:22); “Take no revenge and cherish no grudge against your fellow countrymen. You shall love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord.” (Lv 19:18) Hamlet fails to comprehend or to remember this crucial principle, that a saved soul living in the grace of God in Purgatory could never compel a human being to break God’s Law. Therefore Hamlet fails to realize that the apparition is not of divine origin, but demonic: “the devil… perhaps… abuses me to damn me.” (II, ii, 601-605)

As Hamlet himself writes in The Mousetrap, for the player king impersonating the deceased King Hamlet, “Purpose is but the slave to memory” (III, ii, 179), which also means that human beings cannot act appropriately if they do not remember an essential piece of information because they have erased it from the “table of [their] memory” (I, v, 98) as Hamlet does after the apparition, swearing loyalty to a demon and effectively entering the Satanic Pact.

The effects of the pact with the devil are devastating. As we have seen, after entering the Satanic Pact with the demonic subject Iago, Othello’s reason and intellect are clouded and he is led to destruction and self-destruction. In the same way, Hamlet’s intellectual ability is damaged by the association with a demon, now “grafted” (Rm 11) onto his human spirit. It is therefore with prophetic words – “O my prophetic soul!” (I, v, 41) – that Hamlet describes his oppressed mind as a “distracted globe.” (I, v, 97) The fact that this line is also an autobiographical reference to Shakespeare himself, with his Globe Theater, may indicate that the author knew the spiritual predicament of his protagonist – hence the symbolic title of this section, “in this distracted globe.” The things Hamlet forgets about God and the supernatural bring him to ruin.

As we are going to see in the following discussion, Hamlet as a tragedy has many secrets. This is perhaps the greatest secret of Hamlet and the first thing that Hamlet forgets: forgiveness. To give due honor to God, human beings must live according to God’s Law, and the Logos commands them to forgive: ““This is how you are to pray: ‘Our Father in Heaven, hallowed be Your Name…. and forgive us our debts,/ as we forgive our debtors;/ and do not subject us to the final test,/ but deliver us from the evil one.’ If you forgive others their transgressions, your heavenly Father will forgive you. But if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your transgressions.” (Mt 6:9-15); “Then Peter approaching asked him: ‘Lord, if my brother sins against me, how many times must I forgive him, as many as seven times?’ Jesus answered, ‘I say to you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times. That is why the Kingdom of Heaven may be likened to a king who decided to settle accounts with his servants… The master summoned [the wicked servant] and said: ‘You, wicked servant! I forgave you your entire debt because you begged me to. Should you not have had pity on your fellow servants, as I had pity on you?’ Then in anger his master handed him over to the torturers until he should pay back the whole debt. So will my heavenly Father do to you, unless each of you forgives his brother from the heart.” (Mt 18:21-35)

The law of forgiveness is part of the double commandment of love, toward God and toward the other: “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment. The second is like it. You shall love your neighbor as yourself. The whole Law and the prophets depend on these two commandments.” (Mt 22:37-40); hence the Golden Rule: “Do to others whatever you would have them do to you. This is the Law and the prophets.” (Mt 7:12) This is God’s code of honor, the opposite of man’s code of honor based on pride and revenge.

As in the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25-37) – the Samaritan representing an enemy who rescues a victim left to die on the street – the heart of the Catholic faith is charity toward God and charity and forgiveness toward the other. Also Paul exhorts to be “one in Christ” and “live… in a manner worthy of the call you have received, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another through love, striving to preserve the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace: one Body and one Spirit, as you were also called to the one hope of your call; one Lord; one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.” (Eph 4:1-7) As discussed in Chapter One, Hamlet remembers the beautiful expressions “all in all” to describe his father (I, ii, 186) but not its correct context of forgiveness. The Letter to the Romans expresses the same concept of forgiveness, with the added injunction to obey temporal authority: “Bless those who persecute you, bless and do not curse them… Do not repay anyone evil for evil… live at peace with all. Beloved, do not look for revenge but avoid wrath for it is written, ‘Vengeance is Mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ Rather, if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals upon his head. Do not be conquered by evil, but conquer evil with good. Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God [cf. divine right of kings]” (Rm 12:14-21, 13:1).

This is God’s Law of charity, forgiveness and obedience to the higher authorities that Hamlet tragically “wipe[s] away” from “the table of [his] memory” (I, v, 98-99).

And this is another important secret of Hamlet: the only way for human beings to help penitent souls – not only their family members, friends and acquaintances, but also, with an important act of forgiveness, their deceased enemies – is by indulgence, including holy masses and prayer. There is no other way. The condition of King Hamlet’s soul, if saved, certainly cannot be improved by taking vengeance on a living man or committing other sins against God’s Law, but only by taking indulgences for his liberation and the remission of his sins.

In Catholic orthodoxy, indulgences are important works of mercy both toward the living and the dead. For the living, partial or plenary indulgences are meant for the partial or complete remission of temporal punishment for sins committed; for the dead, they provide liberation from the expiatory punishments of Purgatory.[xix] Indulgences take their efficacy from the infinite merits of the Passion of Christ, as the only “guilt offering” acceptable to the Father on behalf of fallen humanity, cf. 2 Maccabees 12:38-46. As we saw in the dedicated section of Chapter One, the orthodox doctrine of Purgatory and indulgences[xx] is an important theme in Shakespeare, both historically, due to the persecution of Catholics; and artistically, since he symbolically represented this favorite theme in numerous plays including his two masterpieces Hamlet and The Tempest.

It is interesting to notice that both Hamlet and The Tempest are set in the Catholic past and that the protagonists of The Tempest also come from a Catholic country. As a key element of the plot, both plays feature the Divine and the Satanic, e.g. the divine injunction to forgive enemies; angelic Ariel and demonic Caliban, etc. With the practice of indulgences, the faithful demonstrate their good will to follow God’s commandment to love and to forgive others in word and deed: “As you from crimes would pardoned be,/ Let your indulgence set me free.” (The Tempest Epilogue, 19-20) Hence the significance that Shakespeare recognized in this doctrine – quite symbolically, he made it the center-piece of his spiritual testament in Prospero’s Epilogue:

“Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant;

And my ending is despair

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so, that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.”

(The Tempest Epilogue, 13-20)

Greenblatt observed that in Shakespeare’s time, “indulgence” had “the specific, technical sense that it still possesses in Catholic theology: the Church’s spiritual power to remit punishment due to sin;”[xxi] also Beauregard remarked that “[i]n the religious context of Jacobean England and the court of James I, ‘indulgence’ was obviously an important and risky word, a word fraught with powerful theological implications to which Shakespeare could not have been insensitive.”[xxii]

The doctrine of indulgences is crucial to understand Shakespeare’s masterpiece Hamlet and especially the psychology of the “distracted” Prince, which after the Satanic Pact with the “ghost” becomes another instance of what Hazlitt calls “diseased intellectual activity.”[xxiii] Hamlet himself agrees: “My wit’s diseased.” (III, ii, 308) As in Greek tragedy the disparity of knowledge between audience and characters had the welcome effect of creating more pathos – dealing with traditional stories, the audience knew more than the characters – so in Renaissance England, Shakespeare’s audience knew better than the Prince that only indulgences have the power to liberate penitent souls from the post mortem expiation of Purgatory. The same uneven situation that characterizes classical tragedy is masterfully reproduced for Hamlet, with a disparity of knowledge between the audience and the “distracted” Prince that used to make the tragedy even more tragic. As we have seen in Chapter One, Shakespeare uses this device very effectively, making the audience feel in control and at the same time very sorry for the Prince who, by contrast, appears as a tragic example of foolishness. This is especially true if we consider that the name Gertrude is that of an eminent saint and mystic, Gertrude the Great (1256-1302), traditionally associated with indulgences and works of mercy in favor of the penitent souls of Purgatory.[xxiv] Once again, Shakespeare hides essential things in plain sight, in this case the solution to the problem of Hamlet’s revenge and his desire to help his father.

The commoners attending Shakespeare’s Globe in the 16th – 17th century were aware of the facts of religious survival; but after entering the Satanic Pact, Hamlet’s memory and capacity for reason are greatly diminished. After wiping away “all trivial records” (I, v, 99) from his memory, Hamlet does not remember the tragic fate of King Saul (1 Sam 28-31) who was harshly punished by God for conjuring up ghosts, i.e. demons, which is a sin of idolatry against the first commandment inscribed in the Tables – “My tables,/ My tables” (I, v, 107-108) – of the Mosaic Law:

When Saul saw the Philistine camp, he grew afraid and lost heart completely. He consulted the Lord, but the Lord gave no answer, neither in dreams… nor through prophets. Then Saul said to his servants, ‘Find me a medium through whom I can seek counsel.’ His servants answered him, ‘There is a woman in Endor who is a medium.’

So he disguised himself, putting on other clothes, and set out with two companions. They came to the woman at night, and Saul said to her, ‘Divine for me, conjure up the spirit I tell you.’ But the woman answered him, ‘You know what Saul has done, how he expelled the mediums and diviners from the land. Then why are you trying to entrap me and get me killed?’

But Saul swore to her by the Lord, ‘As the Lord lives, you shall incur no blame for this.’ ‘Whom do you want me to conjure up?’ the woman asked him. ‘Conjure up Samuel [the prophet] for me,’ he replied.

When the woman saw Samuel, she shrieked out at the top of her voice and said to Saul, ‘Why have you deceived me? You are Saul!’ But the King said to her, ‘Do not be afraid. What do you see?’ She replied: ‘I see a god rising from the earth.’ ‘What does he look like”’ asked Saul. ‘An old man is coming up wrapped in a robe,’ she replied. Saul knew that this was Samuel, and so he bowed his face to the ground in homage.

Samuel then said to Saul, ‘Why do you disturb me by conjuring me up? […] Why do you ask me if the Lord has abandoned you for your neighbor? The Lord has done to you what he declared through me: he has torn the kingdom from your hand and has given it to your neighbor David. […] Moreover, the Lord will deliver Israel, and you as well, into the hands of the Philistines. By tomorrow you and your sons will be with me, and the Lord will have delivered the army of Israel into the hands of the Philistines.’ Immediately Saul fell full length on the ground, in great fear because of Samuel’s message. (1 Sm 28:5-20)

Because of this sin of idolatry, God punishes Saul by abandoning him to desperation. The king breaks the Mosaic Law again and takes his own life by falling on his sword – “Thus Saul, his three sons, and his armor-bearer died together on the same day” (1 Sm 31:6) in a scene of general massacre like Hamlet’s final scene. It is clear that the Scriptural record greatly influenced Shakespeare in the composition of his masterpiece. “An old man is coming up wrapped in a robe” (1 Sm 28:14) seems to be the Scriptural referent for Hamlet’s “ghost.” Shakespeare also recreates the same effect on the audience/readers. The one question: “Is the spirit conjured up by the medium the actual soul of the deceased prophet Samuel, or is it something else?” mirrors the other: “Is the ghostly apparition the actual soul of the deceased King Hamlet, or is it something else?” It is something else.

As Ophelia laments – “O what a noble mind is here o’erthrown!/ The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’eye, tongue, sword,/ Th’expectancy and rose of the fair state/ The glass of fashion and the mould of form,/ Th’observed of all observers, quite, quite down!” (III, i, 153-157) – Hamlet was on the road to become the perfect Renaissance Prince. Assuming ignorance of Sacred Scripture for Hamlet – or for his audience – is not credible. If the Prince had not “wipe[d] away” from his memory “[a]ll saws of books, all forms, all pressures past” (I, v, 99-100), the historical record of King Saul’s tragic fate would have helped him to understand the reality beyond the deceiving appearances. He would have remembered that from a theological perspective, divination and idolatry are mortal sins against the first commandment – it is a mortal sin to conjure up “ghosts” and/or to obey their injunctions, cf. “thy commandment alone shall live/ Within the book and volume of my brain/ Unmixed with baser matter.” (I, v, 102-104)

All these concepts were quite clear to Renaissance audiences. In addition to Scripture being the only commonly shared text and cultural background for all audiences at the time, particularly after the religious schism, Christianity became a matter of life and death. Hence, beside the Bible, an important text which contributed to popularize the established Catholic orthodoxy on “ghosts” as demonic apparitions, and make it literally common knowledge, was King James’ Daemonologie, in forme of a Dialogue, divided into three Bookes (1597), introduced in Chapter One from a historical perspective with references to the North Berwick witches and the accusations against the Earl of Bothwell.

James’ Daemonologie restates the established Catholic orthodoxy on Demonology, condemning superstition, the practice of magic and “ghostly apparitions” as the work of Satan and his demonic legions. As previously noted (Chapter One, n. 77), his only “innovations” are on the one hand the negation of exorcism as a means to fight demonic agency in human life; and on the other, the projection of the figure of the Great Babylon on Rome and of the Antichrist on the line of Catholic Popes. Without any intellectual tradition to refer to apart from the previous fifteen centuries of Catholic scholarship, it is an established fact of scholarship that James followed the prominent Catholic intellectual Jean Bodin (Démonomanie des Sorciers, 1580) and the Dominicans Krämer and Sprenger – whose Malleus Maleficarum (1486) became, in the centuries to follow, the most influential text for the trial and punishment of many actual practitioners of sorcery (Rev 22:15), and the persecution and martyrdom of many more innocent victims.[xxv] As Silvani remarks, the Daemonologie inevitably had a great impact on contemporary English culture.[xxvi] The book represented the monarch’s definitive political statement on a dangerous and controversial topic, the Satanic Pact and the practice of Satanic magic, which King James saw as a form of terrorism against his person and which caused a number of people both in England and abroad to be accused and “interrogated” – including, as we have seen, the wife of the burgomaster of Copenhagen… As discussed in Chapter One with reference to Ranald’s research on Shakespeare’s socio-cultural context (Shakespeare and His Social Context; Essays in Osmotic Knowledge and Literary Interpretation, 1987), King James’ subjects had a great personal interest, so to speak, in gaining knowledge of what pleased and displeased the monarch.